“O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord” —Ezekiel 37:4-6

Here’s how it happened.

I arrived at Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, Georgia, on Holy Thursday, and found myself in the midst of an Easter Triduum retreat. That evening I attended a talk given by one of the monks and was pierced to the heart. It wasn’t precisely the content of what he said but in what was behind the words: over 60 years in monastic vows, in touch with the latest developments in theology and cosmology, able to spontaneously weave those insights into a lively, engaging conversation—in short, his words and his bearing bore witness to a longstanding, loving commitment to the gift of his vocation. My experience of this encounter prodded and clarified something I’d been wrestling with throughout this tour, and immediately after the talk I sought out the resident spiritual director while the matter was still fresh.

You see, in the retreat house of this monastery there is a room. And within this room sits a woman quietly knitting until someone takes a seat beside her and initiates a conversation. And although she is physically blind, I am convinced that her role within this monastery is analogous to that of the Oracle within the Matrix—the one who sees! I entered the room, poured out my heart, spoke of my longing for that inner wellspring of stability, as well as its outpouring in stable relationships and commitments, and she responded, simply and confidently, “You need to stop. You need a time of stability. You’ve been Martha for so long that you need to take time to be Mary simply sitting at the feet of Jesus. You need to listen to what the God who loves you is communicating to you through all of these experiences.” Specifically, she suggested the monastery’s monastic guest program, wherein I could stay on a month-to-month basis in a work-exchange arrangement, living the monastic rhythms and steeping myself in prayer, silence, community, and simple labor.

At first, I balked at her suggestion. After all, I had responsibilities! I had communities to visit and a podcast to produce! In fact, I had a handful of audio files begging for my attention. How could I let all of that go for even a single month? But the seed had been planted, and after successive visits with her throughout the weekend, on Easter Sunday I decided to take the plunge and spend a month at the monastery. In the meantime, I would have to leave and return in a week. Amazingly, a friend serendipitously offered a house-sitting gig in a small rural town 60 miles away for just that amount of time! I bicycled to her empty house that day, settled in with plenty of coffee, lentils, and rice, and got to business transcribing and editing the last 4 podcast episodes, scheduling their publication in advance, one episode per week, while I remained off-line in the monastery—the first time I’d been able to unplug in a whole year!

In both personal reflections and reflections on community, I’ve kept returning to the themes of stability and commitment. And indeed I think these are the key lines of intersection between the tour of communities and personal pilgrimage, issues that I and so many in our culture struggle with in our lives and relationships, that are so integral to community living. To speak more personally about my own struggles, by my seventeenth birthday I had been placed for adoption twice, endured two divorces in two unrelated families, and for all intents and purposes had no real family left to call my own. I was primed, then, for life in hyper-flux, without stable points of reference or relationship. Ten years later, while on a Zen meditation retreat, all the various living situations I’d had since leaving home began parading themselves before my mind’s eye, and I decided to count them. I was stunned: between the ages of 17 and 27, I had moved 27 times. Yes, I realize that sounds like a virtual mathematical impossibility, and I really don’t know how I managed to move approximately every 4 ½ months. But I did. And this realization was a wake-up call. I needed to learn to live differently.

In the years since that meditation retreat, while I haven’t stayed in one place, I am satisfied that I’ve learned to move more mindfully, and discern wisely where I choose to live and why. However, that moment on retreat wouldn’t be the last time this alarm would ring to alert me that something was amiss in my life, that I needed to change my way of living. In fact, that alarm has been sounding throughout this journey.

Here’s the thing: I didn’t plan to suffer a major loss and disillusionment just before setting out on this tour. I didn’t anticipate that this disillusionment in a personal relationship would spiral inward and, with surgical precision, expose layers of self-delusion, self-defeating motivations, and fantasies that have dominated my life. I could not have foreseen that this journey of self-knowledge would open a seeming abyss beneath my feet, revealing a continuing pattern of a lack of commitment, stability, and intentional engagement that is in fact far more subtle and interior than merely learning to stay in place. And I could not have foreseen the degree to which the communities I’ve visited and the people I’ve met on this tour would serve as intimate mirrors throughout this process, exposing areas of pain and longing in my own life, while pointing to a more fulfilling and fruitful way to live.

I was aware of this emerging inner tumult from the start, and in fact have taken occasional time off the road or from communities, seeking space for reflection, prayer, and guidance. But in each of those instances, the timing seemed somehow off-the-mark, and in any case I was still involved with the podcast and blog. Now, however, at the monastery, rather than relying on my own initiative, I had responded to an unexpected invitation from a spiritual guide to come and rest in God, and with such auspicious liturgical timing! In fact, I do believe that this past Easter Triduum has marked the end of a certain kind of momentum that had been propelling me, and the beginning of a new stage of the journey.

The month in the monastery was a wonderful reprieve from the constant improvisation, adaptation, and unpredictability of the tour. I reveled in the unhindered periods of silence and solitude, while simple manual labor and friendship with the monks provided a necessary, nourishing balance. And of course, I continued to receive wise spiritual guidance throughout. As the time drew nearer to set out on the road again, I had begun to obscurely sense what the whole self-stripping process of this tour has been leading me toward all along: a gentle invitation to entrust myself in faith, hope, and love to the One who had led me though being reduced to a mere pile of disjointed bones, and who was now prepared to weave me back together.

Throughout this journey, I had been under the assumption that the tour of communities was the primary story and the personal pilgrimage the underlying subtext. In truth, the order has been the reverse. I would even go so far as to say that I was likely responding more to the divine invitation to transformation when I began the tour, whether I realized this or not, than to my interest in exploring intentional communities. At the same time, these two aspects of the journey have been deeply interwoven in ways that I anticipate will bear surprising fruit in the months and years to come. However, at this point I cannot anticipate the forms this fruit will take and can only relax into the invitation to trust the wisdom and love that has enfolded these travels all along.

Throughout this journey, I had been under the assumption that the tour of communities was the primary story and the personal pilgrimage the underlying subtext. In truth, the order has been the reverse. I would even go so far as to say that I was likely responding more to the divine invitation to transformation when I began the tour, whether I realized this or not, than to my interest in exploring intentional communities. At the same time, these two aspects of the journey have been deeply interwoven in ways that I anticipate will bear surprising fruit in the months and years to come. However, at this point I cannot anticipate the forms this fruit will take and can only relax into the invitation to trust the wisdom and love that has enfolded these travels all along.

You may be inferring at this point that the tour is over, and if so, you are perhaps partly correct. What has ended, at least this is my hope, is the restless grasping for what-I-do-not-know that has possessed me till this point. What remains is a more playful, open-ended tour of just a handful more communities that I am eager to visit, with no expectations or problems to solve, but with a posture of curiosity and the anticipation of discovery. What remains is a walk in the dark.

On Pentecost Sunday, I pedaled from the monastery with hopefully less baggage than when I arrived. And so the journey rolls on.

I pray…

Lord, thank you for sending your Angel of Disillusionment and the Vultures of Self-Knowledge as my faithful companions throughout my travels. The Angel has ensured that I’ve been stripped of all sense of direction apart from that of unknowing faith, while the Vultures have stripped my flesh to the bone, not even sparing the ligaments.

Lord, thank you for reducing me to a pile of dry bones. I trust that you have something more in mind than that I return from this journey a mere pile of bones on a bicycle seat. Rather, in ways that I cannot see or comprehend from my narrow perch in this strange and fragile human life, I trust that even now you are weaving a new garment of flesh and a new heart, animated by your Breath.

Lord, apart from you I am nothing, can do nothing, can know nothing. You are the question and the response that haunts me in the dark of night. You are the Ray of Darkness that illumines my steps even when I appear to be faltering.

Lord, all that I have and all that I am is yours, and into your hands I entrust all.

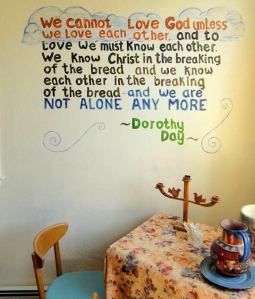

manufacturer, among other activities that make up our daily round. In other words, we live a way of life integrated by and expressive of our deepest faith commitments: following Jesus’ way of solidarity with those on the social margins, economic simplicity and sharing in community, and nonviolent peacemaking.

manufacturer, among other activities that make up our daily round. In other words, we live a way of life integrated by and expressive of our deepest faith commitments: following Jesus’ way of solidarity with those on the social margins, economic simplicity and sharing in community, and nonviolent peacemaking. slowly easing in, finding our place in a core community of four (including ourselves) and a fluctuating community of 4-7 guests, including children! So life for us is good, challenging, hopeful, and we are grateful to have found a concrete way to live out our aspirations. We are clearly on the path I named in my previous post: integrating social action and contemplative practice in community.

slowly easing in, finding our place in a core community of four (including ourselves) and a fluctuating community of 4-7 guests, including children! So life for us is good, challenging, hopeful, and we are grateful to have found a concrete way to live out our aspirations. We are clearly on the path I named in my previous post: integrating social action and contemplative practice in community.